Ultimate (sport)

Ultimate (also called Ultimate Frisbee) is a limited-contact team sport played with a 175 gram flying disc. The object of the game is to score points by passing the disc to a player in the opposing end zone, similar to an end zone in American football or rugby. Players may only move one foot while holding the disc.

While originally called Ultimate Frisbee, it is now officially called Ultimate because Frisbee is the trademark, albeit genericized, for the line of discs made by the Wham-O toy company. In fact, discs made by Wham-O competitor Discraft are the standard discs for the sport. In 2008, there were 4.9 million Ultimate players in the US.[1]

Contents |

Origin

In the fall of 1968, Joel Silver, then a student at Columbia High School proposed a school Frisbee team to the student council on a whim. The following summer, a group of students got together to play what Silver claimed to be the "ultimate game experience," adapting the sport from a form of Frisbee football, likely learned from Jared Kass while attending a summer camp at Northfield Mount Hermon, Massachusetts, where Kass was teaching.[2] The proportion of rules developed by Kass, and those developed by Silver, is disputed. It was discovered in 2003 that the game that Kass and Silver played may have been more similar to Ultimate than had been thought.[3] Regardless, the students who played and codified the rules at Columbia High School in Maplewood, New Jersey, were an eclectic group of students including leaders in academics, student politics, the student newspaper, and school dramatic productions. Key early contributors besides Silver included Bernard "Buzzy" Hellring and Jonny Hines. Another member of the original team was Walter Sabo, who went on to be a major figure in the American radio business. The sport became identified as a counterculture activity.[3] The first definitive history of the sport was published in December 2005, ULTIMATE: The First Four Decades.[4]

While the rules governing movement and scoring of the disc have not changed, the early Columbia High School games had sidelines that were defined by the parking lot of the school and team sizes based on the number of players that showed up. Gentlemanly behavior and gracefulness were held high. (A foul was defined as contact "sufficient to arouse the ire of the player fouled.") No referees were present, which still holds true today: all Ultimate matches (even at high level events) are self-officiated. At higher levels of play 'observers' are often present. Observers only make calls when appealed to by one of the teams, at which point the result is binding.[5]

History of club development

Collegiate clubs

The first collegiate Ultimate club was formed by Silver when he arrived at Lafayette College in 1970.[6]

The first intercollegiate competition was held at Rutgers's New Brunswick campus between Rutgers and Princeton on November 6, 1972, the 103rd anniversary of the first intercollegiate game of American football featuring the same schools competing in the same location.

By 1975, dozens of colleges had teams, and in April 1975, players organized the first Ultimate tournament, an eight-team invitational called the "Intercollegiate Ultimate Frisbee Championships," to be played at Yale. Rutgers beat Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute 26-23 in the finals.

By 1976, teams were organizing in areas outside the Northeast. A 16-team single elimination tournament was set up at Amherst, Massachusetts, to include 13 East Coast teams and 3 Midwest teams. Rutgers again took the title, beating Hampshire College in the finals. Penn State and Princeton were the other semi-finalists. While it was called the "National Ultimate Frisbee Championships", Ultimate was starting to appear in the Los Angeles and Santa Barbara area.

Penn State hosted the first five-region National Ultimate Championships in May 1979. There were five regional representatives: three college and two club teams. They were as follows: Cornell University-(Northeast), Glassboro State- (Middle Atlantic), Michigan State-(Central), Orlando Fling-(South), Santa Barbara Condors-(West). Each team played the other in a round robin format to produce a Glassboro-Condors final. The Condors had gone undefeated up to this point; however Glassboro prevailed 19-18 to become the 1979 national champions. They repeated as champions in 1980 as well.

The first College Nationals made up exclusively of college teams took place in 1984 in Somerville, MA. The event, hosted by the Tufts University E-Men crowned Stanford its winner, as they beat Glassboro State in the finals.[7]

Club and international play

In California, clubs were sprouting in the Los Angeles - Santa Barbara area, while in the east, where the sport developed at the high school and college level, the first college graduates were beginning to found club teams, such as the Philadelphia Frisbee Club, the Washington Area Frisbee Club, the Knights of Nee in New Jersey, the Hostages in Boston and so forth. Arkansas also had a few formidable teams located in the towns of Pocahontas, Newport, and Batesville.

During this time, Ultimate arrived in the United Kingdom, with the UK's first clubs forming at the University of Warwick and the University of Cambridge.[4] By the late 1970s and early 1980s, there were also clubs at the University of Southampton, University of Leicester, and University of Bradford.

Players associations

In 1979 and 1980 the Ultimate Players Association (UPA) was formed. The UPA organized regional tournaments and has crowned a national champion every year since 1979. On May 25, 2010 the UPA rebranded itself as USA Ultimate.

The popularity of the sport spread quickly, taking hold as a free-spirited alternative to traditional organized sports. In recent years college Ultimate has attracted a greater number of traditional athletes, raising the level of competition and athleticism and providing a challenge to its laid back, free-spirited roots.

In 1981 the European Flying disc Federation (EFDF) was formed.[8] In 1984 the World Flying Disc Federation was formed by the EFDF to be the international governing body for disc sports.[8]

Founded in 1986, incorporated in 1993 the Ottawa-Carleton Ultimate Association based in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, claims to have the largest summer league in the world with 354 teams and over 5000 players as of 2004.[9]

In 2006 Ultimate became a BUCS accredited sport at UK universities for both indoor and outdoor open division events.

Games

Traditional Ultimate [10]

By the rules of USA Ultimate, a standard game of Ultimate is played on a field 40 yards wide by 120 yards long, the length of which is divided into a 70 yard playing field with 25 yard end zones at each end. All play is seven on seven, with teams permitted a maximum roster size of 27 players. International WFDF rules use a field with smaller end-zones at 18 meters. There are usually 7, but games are sometimes played with fewer than that number. In mixed Ultimate, at least 3 members of each sex must be on one team at a time.

Play begins with the defensive team (usually determined by flipping two disks, or by rock, paper, scissors) fully within their end zone and the offensive team lined up on their end zone line. The defensive team player throwing the disc raises a hand to signal readiness to begin play. A player on the receiving team raises a hand to signal their readiness to begin play. After both sides have signaled their readiness, the defensive team throws ("pulls") the disc to the other team to begin play. This is equivalent to a kickoff in American football, and happens to start each point.

Once a player catches the disc or the disc is picked up, the player must come to a stop and have one foot planted as a pivot until after passing the disc to another player by throwing it (hand-offs are not permitted). The player has ten seconds to pass the disc, and this “stall” count must be announced, one through ten, by a defensive player within 10 feet of the offensive player in possession of the disc. This is called the "mark." If the ten seconds expire without passing the disc, if the disc is dropped on reception or during possession, if the pass is blocked, intercepted or not caught, or if the disc is thrown out-of-bounds and does not come back in-bounds, possession transfers to the other team, which then becomes the offense.

If a player physically interferes with an opposing player, a foul may be called. If the foul disrupts possession, in most cases the offense regains possession, the ten second count is reset, and play resumes. Because Ultimate is self-refereed, the player who committed the infraction is given the opportunity to contest or accept the call, with somewhat differing results depending on whether or not the player admits fault. If disagreement over a call cannot be resolved, in some instances the play will be repeated. Play is entirely continuous until a score is made, with the exception of stoppages for calls or injuries. Except for injuries, substitutions may be made only between points.

Scores are made by a team successfully completing a pass to a player located in the defensive end zone. After a score, the teams switch their direction of attack, and the scoring team pulls. The game continues until either team reaches 15 points with a two-point margin over their opponents, or until either team reaches 17 points total. This can be adjusted by captains or tournament organizers. Tournament games are often to 13. A ten-minute halftime break occurs when either team reaches eight points total. Alternatively, the game can be played (as is the custom for most other sports) until a particular time limit has elapsed. More commonly, the game is played for a given time, at the end of which a 'soft cap' is played: the winner is the team to reach a score one greater than the current highest score (i.e., the team in the lead has to score once, or the other team has to catch up, equalise, and then score once). Each team may call up to two 70-second time-outs per half. During play, time-outs may be called only by the player in possession of the disc. Any player may call a time-out in between points. Each team is allowed to call one and only one time-out once the score reaches 14-14.

Sportsmanship, respect for other players, fair play, and having fun are considered central aspects of play, even when competition becomes intense. This is called "spirit of the game."

Indoor Ultimate

Ultimate is sometimes played on an indoor football (soccer) field. If the field has indoor football markings on it, then the outer most goal box lines are used for endzone lines. Playing off the walls or ceiling is usually not permitted. Since indoor venues tend to be smaller, the number of players per side is often decreased. Depending of the size of the field, two types of game can be played : 4 on 4 or 5 on 5.

Some indoor leagues play Speedpoint, also known as Quebec City rules (4 on 4), in order to speed up play:

- Only 2 pulls every game: at the beginning of the game and after halftime. Each team pulls once.

- After a point is scored, play resumes from the point in the end zone where the point was scored.

- Maximum 20 second delay between the scoring of a point and the beginning of the next one.

- Players may only substitute between points.

- Each team is allowed one timeout per game.

- Timeouts cannot be called in the last 5 minutes of the game.

- In 5 on 5, substitutions are allowed on the fly (while playing)

Indoor Ultimate is played widely in Northern Europe during the winter because of frigid weather conditions.

In North America, indoor Ultimate tends to be played in venues that can accommodate a field of regular or near-regular size and the playing surface is AstroTurf or some other kind of artificial grass.

In Europe, on the other hand, such facilities are rarely available, and indoor Ultimate is usually on a handball or basketball court. In northern European and Scandinavian countries handball courts are the norm, whereas in the UK, Russia, and Southern Europe, basketball courts are more commonly used. Players often wear protection such as knee, elbow and wrist pads, much like in volleyball to avoid bruises and cuts when laying out.

European indoor Ultimate has evolved as a variant of standard outdoor Ultimate. Because of the small size of the court and of the absence of wind, several indoor-specific offensive and defensive tactics have been developed. Moreover, whereas throws such as scoobers, blades, hammers, and push-passes are rarely used or discouraged outdoors because even a little wind makes them inaccurate or because they are effective only at short range, but they are common in the small and wind-free indoor courts. The stall count is reduced to 8 seconds because of the faster nature of the indoor game.

There are regular indoor tournaments and championships and stable indoor teams. The best-known and longest-running indoor tournament is the Skogshyddan's Vintertrofén held in Gothenburg, Sweden, every year.

Beach Ultimate

Beach Ultimate is a variant of this activity. It is played in teams of four or five players on small fields. It is played on sand and, as the name implies, normally at the beach. Players may be barefoot. The Beach Ultimate Lovers Association (BULA) is the international governing body for beach Ultimate.

Most beach Ultimate tournaments are played according to BULA rules, which are based on WFDF rules with a few modifications.

The largest[11] and one of the most notable beach Ultimate tournaments is the co-ed tournament held annually in July at Wildwood, New Jersey. Another well known tournament is Paganello in Rimini, Italy.

Intense Ultimate

Intense Ultimate is a version of Ultimate made to play on a smaller field than regular Ultimate. It was devised as a way to play Ultimate in an urban setting for people who may not have enough space or grass to play regular Ultimate. It is like indoor Ultimate in many respects, including that games are usually played with 6 to 12 players. Below is a brief summary of the rules:

- There is only one end zone.

- The end zone line is divided into three equal parts and demarcated, but the end zone behind it remains whole.

- To score a point, the disc must be thrown so that it passes over the inner part of the end zone line and be caught in the end zone.

- If the disc is thrown so that it passes over the outer parts of the end zone line and is caught anywhere in the end zone, the offensive team does not receive a point, but rather continues play. They must pass the disc back onto the court before they may score a point by throwing the disc so that it passes over the inner part of the end zone line and catching the disc in the end zone.

- Points awarded for catching the disc in the end zone are counted just as in regular Ultimate. The disc can be caught anywhere in the end zone.

- On the opposite side of the field from the end zone is a transfer zone.

- Catching the disc in the transfer zone makes your team eligible to score in the end zone. Otherwise, your team cannot score in the end zone. Gaining possession in the transfer zone counts as a catch in the transfer zone.

- Once a team is eligible to score, it remains eligible to score until the opposing team catches the disc in the transfer zone, regardless of any changes of possession.

- There is no pull (starting the game with a throw to the other team). Instead, the scoring team hands the disc to the opposing team, who starts from the transfer zone. This counts as it being caught in the transfer zone. The team has 20 seconds to start after a score is made.

Street Ultimate

Street Ultimate, which is also known as Street Style, is a less formal variant of Ultimate and is usually carried out similar to a pick-up game. Since there is no set player limit, teams sizes are based on the number of people present. Formalities are usually disregarded as it is a slightly rougher style of Ultimate.

Strategy and tactics

Offense

Players employ many different offensive strategies with different goals. Most basic strategies are an attempt to create open lanes on the field for the exchange of the disc between the thrower and the receiver. Organized teams assign positions to the players based on their specific strengths. Designated throwers are called handlers and designated receivers are called cutters. The amount of autonomy or overlap between these positions depends on the make-up of the team.

One of the most common offensive strategies is the vertical stack. In this strategy, the offense lines up in a straight line along the length of the field. From this position, players in the stack make cuts (sudden sprints out of the stack) towards or away from the handler in an attempt to get open and receive the disc. The stack generally lines up in the middle of the field, thereby opening up two lanes along the sidelines for cuts, although a captain may occasionally call for the stack to line up closer to one sideline, leaving open just one larger cutting lane on the other side.

Another popular offensive strategy is the horizontal stack. In the most popular form of this offense, three handlers line up across the width of the field with four cutters upfield, spaced evenly across the field. This formation encourages cutters to attack any of the space either upfield or downfield of the stack, granting each cutter access to the full width of the field and thereby allowing a degree more creativity than is possible with a vertical stack. If cutters cannot get open, the handlers swing the disc side to side in an attempt to reset the stall count while also getting the defense out of position.

A variation on the horizontal stack offense is called a feature, or German. In this offensive strategy three of the cutters line up deeper than usual (this can vary from 5 yards farther down field to at the endzone) while the remaining cutter lines up closer to the handlers. This closest cutter is known as the "feature," or "German." The idea behind this strategy is that it opens up space for the feature to cut, and at the same time it allows handlers to focus all of their attention on only one cutter. This maximizes the ability for give-and-go strategies between the feature and the handlers. It is also an excellent strategy if one cutter is superior to other cutters, or if he is guarded by someone slower than him. While the main focus is on the handlers and the feature, the remaining three cutters can be used if the feature cannot get open, if there is an open deep look, or for a continuation throw from the feature itself. Typically, however, these three remaining cutters do all they can to get out of the feature's way.

A third common offensive strategy is the spread, or split stack. The spread offense features three handlers in the same formation as for a horizontal stack, and four downfield cutters. Cutters split into two-person teams near both sidelines at the same distance from the handlers as in the horizontal stack. The first cut can come from either sideline, then usually moves into the center of the field before moving upfield or downfield. The second cut can also come from either sideline, and will usually cut in the opposite direction (downfield or upfield) as the first cut. The spread strategy creates a large lane in the middle of the field in which the active cutter is looking to make one big play in or out before clearing back to one of the sidelines.

A fourth, less common strategy is called the hybrid, because it creates two-person teams of cutters just as in the split stack, but one of these two-person teams plays as a vertical stack on one side of the field. Handlers arrange themselves as in a horizontal stack. The advantage of the hybrid is that one of the two-person teams makes use of the large open lane created in the middle of the field just as in the split stack offense, while the other two-person team has one person ready to make a continuation cut and one person ready to make an additional cut to the handlers.

Many advanced teams develop variations on the basic offenses to take advantage of the strengths of specific players. Frequently, these offenses are meant to isolate a few key players in one-on-one situations, allowing them more freedom of movement and the ability to make most of the plays, while the others play a supporting role.

In all of these strategies, players making cuts have two major options in how they cut. They may cut in towards the disc and attempt to find an open avenue between defenders for a short pass, or they may cut away from the disc towards the deep field. The deep field is usually sparsely defended but requires the handler to throw a huck (a long down field throw).

Defense

Force

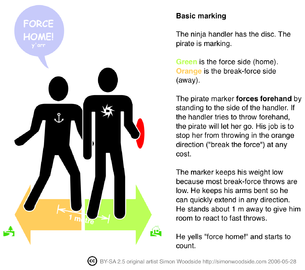

One of the most basic defensive principles is the force. The marker effectively blocks the handler's access to half of the field, by aggressively blocking only one side of the handler and leaving the other side open. The unguarded side is called the force side because the thrower is generally forced to throw to that side of the field. The guarded side is called the break-force side, or simply break side, because the thrower would have to "break" the force to throw to that side.

This is done because, assuming evenly matched players, the handler is considered to have an advantage over the marker. It is considered to be relatively easy for the handler to fake out or outmaneuver a marker who is trying to block the whole field, and thus be able to throw the disc. Alternatively, it is generally possible to effectively block half of the field.

The marker calls out the force side ("force home" or "force away") before starting the stall count in order to alert the other defenders to which side of the field is open to the handler. The team can choose the force side ahead of time, or change it on the fly from throw to throw. Aside from forcing home or away, other forces are "force sideline" (force towards the closest sideline), "force center" (force towards the center of the field), and "force up" (force towards either sideline but prevent a throw straight up the field). Another common tactic is to "force forehand" (force the thrower to use their forehand throw) since most players, especially at lower levels of play, have a stronger backhand throw. "Force flick" refers to the forehand; "force back" refers to the backhand.

When the marker calls out the force side, the team can then rely on the marker to block off half the field and position themselves to aggressively cover just the open/force side. If they are playing one-to-one defense, they should position themselves on the force side of their marks, since that is the side that they are most likely to cut to.

The opposite of the "force" is the "straight-up" mark (also called the "no-huck" mark). In this defense, the player marking the handler positions himself directly between the handler and the end zone and actively tries to block both forehands and backhands. Although the handler can make throws to either side, this is the best defense against long throws ("hucks") to the center of the field.

One-on-one defense

The simplest defensive strategy is the one-on-one defense (also known as "man-on-man", "man-to-man", simply "man", or "person"), where each defender guards a specific offensive player, called their "mark". The one-on-one defense emphasizes speed, stamina, and individual positioning and reading of the field. Often players will mark the same person throughout the game, giving them an opportunity to pick up on their opponent's strengths and weaknesses as they play. One-on-one defense can also play a part role in other more complex zone defense strategies.

Zone defense

With a zone defense strategy, the defenders cover an area rather than a specific person. The area they cover moves with the disc as it progresses down the field. Zone defense is frequently used when the weather is windy, rainy, or snowy. The zone defense is also used to discourage the offense from making long passes. A zone defense usually has two components. The first is a group of players close to the disc who attempt to contain the offenses' ability to pass and prevent forward movement. The "zone" is sometimes called the "wedge", "cup", "wall", or "clam" (depending on the specific play or type of zone defense). These close defenders always position themselves relative to the disc, meaning that they have to move quickly as it passes from handler to handler.

Wedge

The wedge is a configuration of two close defenders. One of them marks the handler with a force, and the other stands away and to the force side of the handler, blocking any throw or cut on that side. The wedge allows more defenders to play up the field but does little to prevent cross-field passes.

Cup

The cup involves three players, arranged in a semi-circular cup-shaped formation, one in the middle and back, the other two on the sides and forward. One of the side players marks the handler with a force, while the other two guard the open side. Therefore the handler will normally have to throw into the cup, allowing the defenders to more easily make blocks. With a cup, usually the center cup blocks the up-field lane to cutters, while the side cup blocks the cross-field swing pass to other handlers. The center cup usually also has the responsibility to call out which of the two sides should mark the thrower, usually the defender closest to the sideline of the field. The idea of the cup is to force the offense into making many short passes behind and around the cup. The more times the offense is forced to throw the greater the chance that the handlers will make a bad throw, or a defender will intercept the disc. The other four defenders traditionally play as two wings, who each cover a sideline, a middle sometimes referred to as a "middle-mid" or "popper d" who covers directly behind the cup for any short throws through or over the cup, and a deep, who covers any long throws by the offense.

Wall

The "wall" sometimes referred to as the "1-3-3" involves four players in the close defense. One player is the marker, also called the "rabbit", "chaser" or "puke" because they often have to run quickly between multiple handlers spread out across the field. The other three defenders form a horizontal "wall" or line across the field in front of the handler to stop throws to short in-cuts and prevent forward progress. The players in the second group of a zone defense, called "mids" and "deeps", position themselves further out to stop throws that escape the cup and fly up field. Because a zone defense focuses defenders on stopping short passes, it leaves a large portion of the field to be covered by the remaining mid and deep players. Assuming that there are seven players on the field, and that a cup is in effect, this leaves four players to cover the rest of the field. In fact, usually only one deep player is used to cover hucks (the "deep-deep"), with two others defending the sidelines and possibly a single "mid-mid".

Alternately, the mids and deeps can play a one-to-one defense on the players who are outside of the cup or cutting deep, although frequent switching might be necessary.

Junk defense

A junk defense is a defense using elements of both zone and man defenses; the most well-known is the "clam" or "chrome wall". In clam defenses, defenders cover cutting lanes rather than zones of the field or individual players. The clam can be used by several players on a team while the rest are running a man defense. Typically, a few defenders play man on the throwers while the cutter defenders play as "flats", taking away in cuts by guarding their respective areas, or as the "deep" or "monster", taking away any deep throws.

This defensive strategy is often referred to as "bait and switch". In this case, when the two players the defenders are covering are standing close to each other in the stack, one defender will move over to shade them deep, and the other will move slightly more towards the thrower. When one of the receivers makes a deep cut, the first defender picks them up, and if one makes an in-cut, the second defender covers them. The defenders communicate and switch their marks if their respective charges change their cuts from in to deep, or vice versa. The clam can also be used by the entire team, with different defenders covering in cuts, deep cuts, break side cuts, and dump cuts.

The term "junk defense" is also often used to refer to zone defenses in general (or to zone defense applied by the defending team momentarily, before switching to a man defense), especially by members of the attacking team before they have determined which exact type of zone defense they are facing.

Spirit of the Game

Ultimate is known for its "Spirit of the Game", often abbreviated SOTG. Ultimate's self-officiated nature demands a strong spirit of sportsmanship and respect. The following description is from the official Ultimate rules established by the Ultimate Players Association:

Ultimate has traditionally relied upon a spirit of sportsmanship which places the responsibility for fair play on the player. Highly competitive play is encouraged, but never at the expense of the bond of mutual respect between players, adherence to the agreed upon rules of the game, or the basic joy of play. Protection of these vital elements serves to eliminate adverse conduct from the Ultimate field. Such actions as taunting of opposing players, dangerous aggression, intentional fouling, or other 'win-at-all-costs' behavior are contrary to the spirit of the game and must be avoided by all players.

Many tournaments give awards for the most spirited team, as voted for by all the teams taking part in the tournament.

Competition

Pick-up games

There are many types of pick-up. Often this consists of tournaments played outside the championship circuit, including hat tournaments, in which teams are selected on the day of play by picking names out of a hat. These are generally held over a weekend, affording players several games during the day as well as the chance to socialize at night. Pick-up leagues also exist, hosting weekly pick-up games that may be played on arbitrary week nights. In addition, less formal games of pick-up are frequent in parks and fields across the globe. In all these types of pick-up games it will not be uncommon to have as participants the same people who play on nationally or globally competitive teams. Newcomers are always welcomed at pick-up games or whenever people are simply throwing, and enthusiastic players will sideline themselves to spend time teaching beginners the throws and maneuvers necessary to play.

Hat tournaments

Hat tournaments are common in the Ultimate circuit. They are tournaments where players join individually rather than as a team. The tournament organizers form teams by randomly taking the names of the participants from a hat.

However, in some tournaments, the organizers do not actually use a hat, but form teams taking into account skill, experience, sex, age, height, and fitness level of the players in the attempt to form teams of even strength. A player provides this information when he or she signs up to enter the tournament. There are also many cities that run hat leagues, structured like a hat tournament, but where the group of players stay together over the course of a season.

In both hat leagues and hat tournaments, there is an emphasis on forming new connections throughout the Ultimate community. Hat tournaments have a strong emphasis on having fun, socializing, partying, and meeting other players. Players of all levels take part in such events from world-class players to complete beginners. Hat tournaments (and sometimes also regular tournaments) often have a theme, such as wild west, aliens, pirates, superheroes, etc. The organizers often name teams also according to a theme, such as: beer varieties, movie characters, etc.

Current leagues

Regulation play, sanctioned in the United States by the UPA, occurs at the college (open & women's divisions), club (open, women's, mixed (co-ed), masters and grandmasters divisions) and youth (boys & girls divisions) levels, with annual championships in all divisions. Top teams from the championship series compete in semi-annual world championships regulated by the WFDF (alternating between Club Championships and National Championships), made up of national flying disc organizations and federations from about 50 countries.

Recreational leagues have become widespread, and range in organization and size. There have been a small number of children's leagues. The largest and first known pre-high school league was started in 1993 by Mary Lowry, Joe Bisignano, and Jeff Jorgenson in Seattle, Washington.[12] In 2005, the discNW Middle School Spring League had over 450 players on 30 mixed teams. Large high school leagues are also becoming common. The largest one is the discNW High School Spring League. It has both mixed and single gender divisions with over 30 teams total. The largest adult league is the San Francisco Ultimate League, with 350 teams and over 4000 active members in 2005, located in San Francisco, California. Dating back to 1977, the Mercer County (New Jersey) Ultimate disc League (mcudl.org) is the world's oldest recreational league. There are even large leagues with children as young as third grade, an example being the junior division of the SULA Ultimate league in Amherst, Massachusetts.

High school and junior leagues

Tournaments at the high school level of play range from tournaments hosted by local teams to tournaments at a national level. USA Ultimate hosts the Men and Women's HS national championships every year in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This tournament is known as Youth Club Championships, or YCC's, and often features at-large teams (different players from within a large area such as New England), no single high school team attends.

The most prestigious tournaments for high school teams in the United States splits the championships between the East and West Coast. The tournaments are known as Eastern's and Western's and are becoming more competitive as high school programs are beginning to treat the game of Ultimate more seriously. The UPA also hosts a national Junior's club team tournament and sends a representative team to the World Junior Ultimate Championships, held every two years. At a lower level, the UPA has also sanctioned organized statewide tournaments in 20 states.

In the United Kingdom, there were over 20 teams attending this years Junior Nations (including a coach's team, who played purely for fun), which were held in Sutton Coldfield Birmingham. This event was run by Andrew Vaughan, the coach of the largest Junior team currently in the UK, Arctic Ultimate. Many of the pupils also play for their national teams Great Britain Juniors. With a continuation of the popularity of Ultimate a possibility of it being introduced into further high schools making a more competitive league in the UK for junior Ultimate players.

College teams and Club teams

There are over 12,000 student athletes playing on over 700 college Ultimate teams in North America,[13], and the number of teams is steadily growing. Separated into Open (nearly 450 teams) and Women's (around 200 teams) Divisions, teams compete in the USA Ultimate College Championship series during the spring. The series consists of 3 tournaments: sectionals, regionals, and nationals. Each year, the top teams from sectionals move on to regionals. The regional champion, runner-up, and possibly a strength bid, advance to Nationals to compete for the championship title in May. College teams have for years been trying to get the sport accepted to NCAA status, without success.

USA Ultimate Club Ultimate consists of Open, Women's, Masters, Youth and Mixed divisions. Club also has regional championships and a national championship, but it also has international competition. The 2010 World Ultimate Club Championships were held in Prague, Czech Republic in July 2010.

Major tournaments

- World Games, international tournament attended by national teams; organized by the WFDF. 2009 tournament link.

- World Ultimate & Guts Championships, international tournament attended by national teams; organized by the WFDF. 2008 tournament link.

- World Ultimate Club Championships, international tournament attended by club teams; organized by the WFDF. 2010 tournament link.

- World Junior Ultimate Championships, international tournament attended by national junior teams; organized by the WFDF. 2010 tournament link.

- UPA Championship Series, an American and Canadian tournament series attended by regional teams; organized by the UPA. Championship Series link.

- European Ultimate Championships, European tournament attended by national teams; organized by the EFDF. 2007 tournament link.

- European Ultimate Club Series, European tournament attended by club teams that qualify at the European Ultimate Championships in their region; organized by the EFDF. 2006 tournament link.

- European Ultimate Club Championships, European tournament attended by club teams every 4 years; organized by the EFDF.

- Spring Reign, an annual youth Ultimate Tournament held in Burlington, Wa. Organized by discNW, Spring Reign is the largest youth Ultimate tournament in the world. Spring Reign Website

- Chennai Heat, India's largest Beach Terrain Tournament, held in Chennai. Its the most competitive tournament in India. [1]

Beach Ultimate tournaments

- World Championship Beach Ultimate 2007 [2]. The 2nd 5-on-5 Beach Ultimate World Championship for national teams. Held in December 2007 in Brazil. Organized by Federação Paulista de Disco with the collaboration of BULA.

- European Championship Beach Ultimate [3] European tournament attended by national teams; organized by BULA.

- Paganello, unofficial Beach Ultimate club world cup, held every year on Easter weekend in Rimini, Italy.

- yes BUT Nau, in Le Pouliguen, France, held every year on the Pentecost/Whit Monday holiday (May/June), organized by the Frisbeurs Nantais.

- Burla Beach Cup. A large tournament, in 2006 hosted 70 teams, held every year in September in Viareggio, Tuscany, Italy. Organized by the Tuscan Flying Bisch Association.

- CUBE Caledonia's Ultimate Beach Event. The University of Aberdeen's BULA affiliated open beach Ultimate competition held annually in April.

- Wildwood, the largest annual beach Ultimate tournament in the world, held in Wildwood, New Jersey.

- Sandblast, an annual beach Ultimate tournament held in early July located in Chicago, Illinois.

- TBUF, the longest running annual beach Ultimate tournament in the world (since 1986) held in mid June located in Galveston, Texas.

- Lei-Out. Held in late January in Los Angeles, California.

See also

- List of Ultimate teams

- disc golf

- disc throws

- Flying disc games

- World Flying Disc Federation

- Beach Ultimate Lovers Association

- Deutscher Frisbeesport-Verband

- U.S. intercollegiate Ultimate champions

References

- ↑ Rovell, Darren (April 9, 2009). "Ultimate Frisbee On The Rise". cnbc.com. http://www.cnbc.com/id/30138012. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Interview with Jared Kass | Ultimate Players Association newsletter, Winter 2003 via ultimatehalloffame.org

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Origins and Development of Ultimate Frisbee, Griggs, Gerald. The Sports Journal. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Leonardo, Tony; Zagoria, Adam (2005). ULTIMATE: The First Four Decades. Ultimate History, Inc.. ISBN 0-9764496-0-9.

- ↑ "For Observers". Ultimate Players Association. http://www2.upa.org/observers. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ "Collegiate Ultimate Frisbee Began at Lafayette". www.lafayette.edu. http://www.lafayette.edu/news.php/view/167. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ Leonardo, Pasquale Anthony; Adam Zagoria (2005). ULTIMATE--The First Four Decades. Ultimate History, Inc. (Joe Seidler). ISBN 9780976449607.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Timeline of Early History of Flying disc Play (1871-1995)". Wfdf.org. http://www.wfdf.org/index.php?page=history/timeline.htm. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ OCUA

- ↑ "Ultimate in 10 Simple Rules". http://www.usaultimate.org/resources/officiating/rules/. and the "Official Rules - 11th Edition". http://www.upa.org/ultimate/rules/11th. Reviewed July 10, 2009.

- ↑ http://www.wildwoodultimate.com/ Wildwood tournament website

- ↑ Bock, Paula (July 24, 2005). "The Sport Of Free Spirits". The Seattle Times Sunday Magazine (Seattle, Washington: The Seattle Times company). http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/pacificnw07242005/coverstory.html. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ USA Ultimate College Championships

External links

Rules

- WFDF rules (worldwide, except Americas, and Worlds championship)

- The Complete 11th Edition of the Rules of Ultimate, Approved 01/11/2007 (Americas)

- 5 on 5 and 4 on 4 Beach Ultimate

- Ultimate Frisbee Rules.org General Ultimate Frisbee Rules

Leagues and Associations

- USA Ultimate (formerly Ultimate Players Association)

- World Flying Disc Federation (WFDF)

- Beach Ultimate Lovers Association (BULA)

- European Flying disc Federation (EFDF)

- Irish Flying disc Association (IFDA)

- UK and Ireland Ladder League

- UK Ultimate association(UKUA)

- Canadian Ultimate Players Association (CUPA)

- Flying disc Federation of Pakistan (FDFP)

- New Zealand Ultimate (NZU)

- Slovak Association of frisbee (SAF)

- Asociacion de Jugadores de Ultimate en Colombia(AJUC)

Venues

- USA Ultimate's list of Teams, Pickup, Leagues, and Tournaments

- PickupUltimate.com - a Google Map mashup of pickup games

- FFindr.com - find frisbee anywhere

- Cultimate - Ultimate Tournament Management

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||